Job’s Relationship With God: Discovering truth in lament

Jo Acharya | May 19, 2022

What did Job get right about God? That’s the question I’m left with at the end of his story. Job is a good man who has lost everything, and he doesn’t know how to explain his suffering, except to assume that God is against him. He cries out in distress, accusing his creator of cruelty, injustice and violence towards him. His speeches are hard to read because they come from a place of such intense pain.

I can see why God doesn’t condemn Job’s anguished words, and I can see why he speaks so harshly at the end to Job’s three friends, who have spent the whole book kicking a guy when he’s down. But God’s final declaration is still a puzzle:

After the LORD had said these things to Job, he said to Eliphaz the Temanite, ‘I am angry with you and your two friends, because you have not spoken the truth about me, as my servant Job has.’

So what can we learn from Job’s relationship with God? What did he get right that his friends didn’t?

Battle of the Psalms

The book of Job could really have been titled ‘Battle of the Psalms’. When I read it recently I was struck by how much Job’s words reminded me of the psalms of lament:

I have sewed sackcloth over my skin and buried my brow in the dust.

My face is red with weeping, dark shadows ring my eyes;

yet my hands have been free of violence and my prayer is pure.

I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint.

My heart has turned to wax; it has melted within me.

My mouth is dried up like a potsherd, and my tongue sticks to the roof of my mouth;

you lay me in the dust of death.

So Job is in good company. But wait – we can’t just dismiss what the friends say, because their words echo other psalms that speak of God’s righteous justice:

Do not fret because of those who are evil or be envious of those who do wrong;

for like the grass they will soon wither, like green plants they will soon die away.

Trust in the LORD and do good; dwell in the land and enjoy safe pasture.

Take delight in the LORD, and he will give you the desires of your heart.

If you put away the sin that is in your hand and allow no evil to dwell in your tent,

then, free of fault, you will lift up your face; you will stand firm and without fear.

But the eyes of the wicked will fail, and escape will elude them;

their hope will become a dying gasp.

Job speaks out of his torment, with speeches that are personal and full of emotion. His friends bring the abstract theology: God rewards good and punishes evil. In their minds, it’s neat and tidy. If you’re suffering, they think, it must be because you’ve done something wrong.

But this is where they make their mistake. The psalms that Job’s friends look to are principles for living and expressions of hope. They are not weapons to be used against hurting people. “Stay the course”, these psalms urge, “Don’t give up, because God is good and he will make everything right.” The truth that God will one day reward good and punish evil does not lead to the easy conclusion that those who suffer are always at fault. Job’s friends are the Bible’s own Bible bashers. They wield the word of God like a fly-swatter, a tool with which to squash uncomfortable realities.

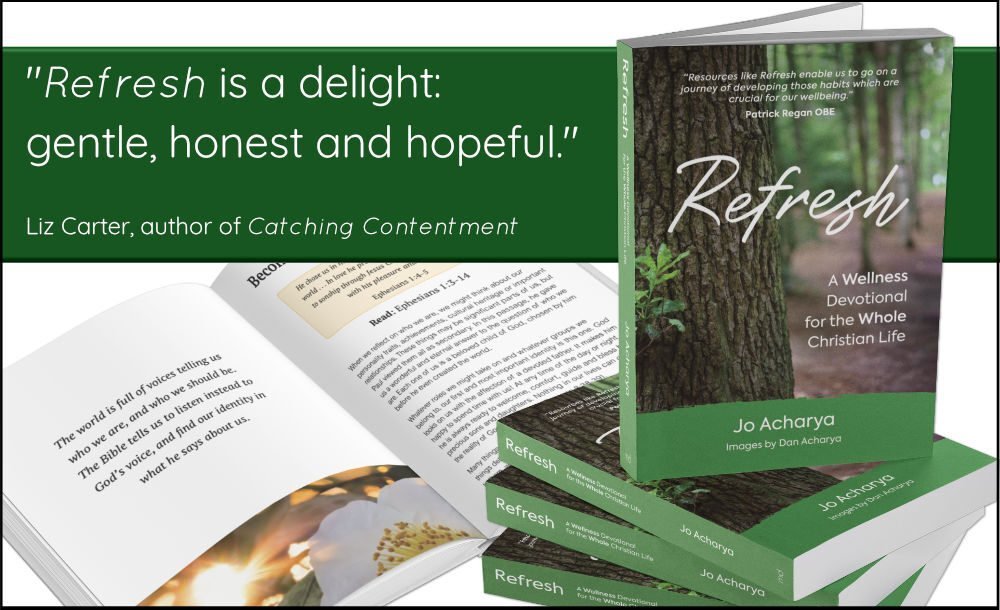

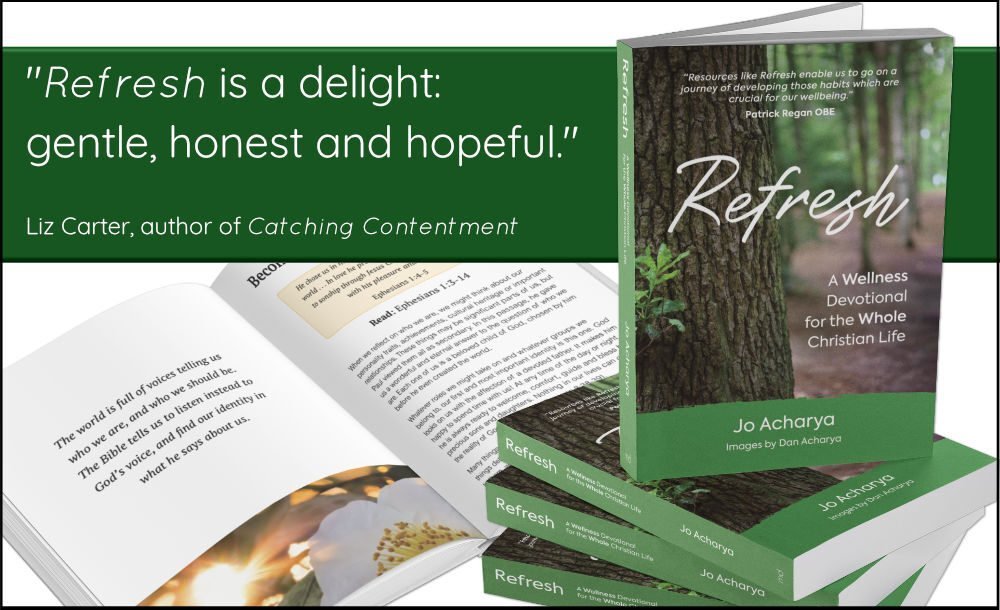

David the psalmist knew that life was complex. He wrote both Psalm 22 and Psalm 37. He trusted in God’s goodness and justice, but he also knew that life could be hard, confusing and painful. So it matters how we apply the wide variety of writings we call sacred. In my book ‘Refresh’ I explore how David’s psalms give us a valuable model for openness and honesty with God. David shows us that when faced with suffering and pain, the appropriate response is lament.

But none of this quite answers the question. How did Job tell the truth about God?

What kind of God is this, anyway?

Job’s friends have a distant view of God. He is a righteous judge somewhere up there and we can’t possibly question him. He doesn’t have to account for himself and it’s almost unthinkable that he ever would. So they don’t expect a response from God. In fact, they don’t even speak to him. They only speak about him.

Job relationship with God is very different. This distant, impersonal view of God is not enough for him. Perhaps it has been in the past; to begin with, he stoically accepts his suffering and doesn’t entertain the idea that he might challenge God. But as time goes on, Job’s two-dimensional, neat and tidy theology crumbles. And then he talks to God. He complains to God. He shouts and rants at God. He pleads with God. He finds he needs God to be personal. He needs God to be the kind of god who will respond. This is what his friends find threatening.

Job says a lot about God that isn’t true. But lament takes him to a deeper, more vulnerable quality of faith that his friends simply can’t handle. Job’s relationship with God evolves into something more expansive, more accurate, more true. God is the kind of god that Job desperately needs him to be. He is personal, and he does respond. Through his cries of distress, Job declares and discovers the truth that God is closer than he or his friends have ever imagined.

God could have condemned Job for all the inaccurate and offensive statements he had made about him. But instead he praised him for the one thing that really mattered. Job didn’t give up. He told God exactly how he felt and expected him to care. Our Father is not the distant, two-dimensional God of Job’s friends. He is the personal, close and responsive God of Job. Job’s relationship with God teaches us that radical honesty with our creator can lead to deeper connection, greater understanding and stronger faith.

If you found this article helpful, you might enjoy my book ‘Refresh’. It’s a beautiful devotional journal exploring God’s plan for living well in every area of life. The 52 short reflections are filled with Biblical wisdom and gentle encouragement for the everyday. Get a signed copy in our store, or pick it up on Amazon (affiliate link).